Skip to content

Skip to content

The Tramp Art Origin Story Isn’t What You’ve Likely Been Told (The Real One Involves The IRS!)

Every article I’ve ever read about Tramp Art starts out something like this: “Have you seen this art? It’s grotesque! It’s hideous! It’s so ugly, it’s beautiful! Can you believe this awkward and/or magnificent piece was carved by some hobo in exchange for a can of beans?”

You can almost hear the banjo twang under the headline. It’s the kind of story America loves to tell about itself – a tale of grit and ingenuity, wrapped in a little hardship and a lot of myth. A nameless drifter! A pocket knife! A railroad! A miracle of folk creativity born from nothing but hunger and cedar! It’s a compelling story. It’s also a lie.

The real story of Tramp Art doesn’t start with a hobo and a can of beans – it starts with the IRS. (Because of course it does. This is America, after all.) And like most stories that involve the IRS, it only gets weirder from here. Ready to dispel the myth?

What Even Is Tramp Art?

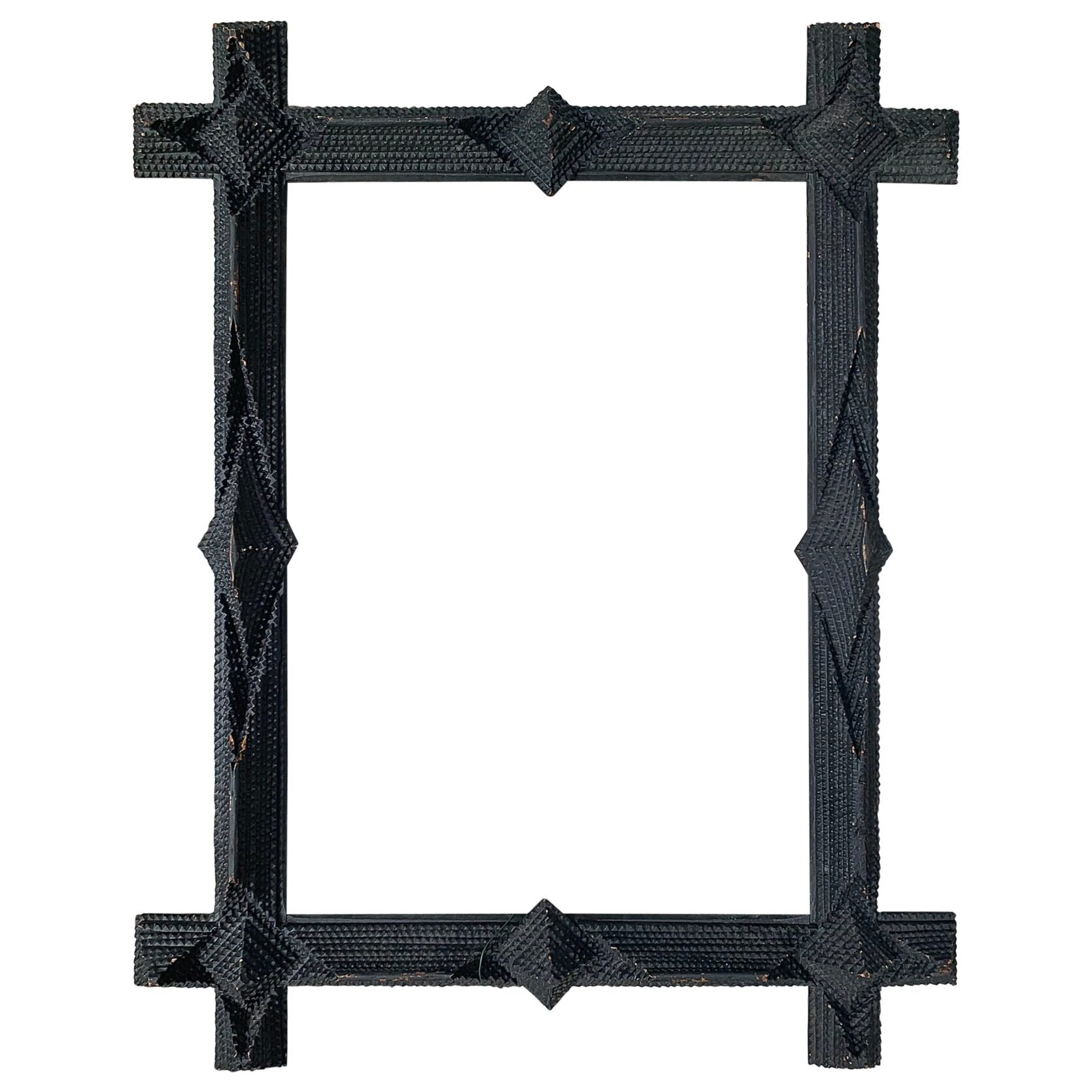

19th-century Tramp Art Mirror, $6,726.70

Tramp Art looks like what happens when someone gives a perfectionist a pocketknife and a little too much time. The pieces are covered in repeating notches, layers, and angles – they’re a little gothic, a little homemade, and completely hypnotic. (How anyone could describe the above as “unsightly” is beyond me – we have slandered our homegrown crafts for far too long!)

Tramp Art was born from the great American tradition of making do – nothing went to waste if it could be turned into something else. People built with whatever they had on hand – bottle caps, cigar boxes, spools, crates, even the occasional scrap of tin or bone. (Folk art from this era presents like a census of what was lying around the house. I’m focusing on the wooden pieces today, but would happily write a similar novel on the bottle cap bowl.) Tramp Artists created everything from tiny ring boxes and picture frames to full-sized grandfather clocks and vanities. The work is maximalist. It’s fussy. It should not work. It completely works.

Historians have sometimes referred to the whole practice as “men’s quilting.” The materials were different – cedar and glue instead of cotton and thread – but the impulse was the same: take scraps, sit down, and make something beautiful and useful for the home.

The Big Myth: “Tramps Made This”

Despite the name, Tramp Art wasn’t made by tramps. Or transients. Or hobos. Or anyone of that ilk, hopping trains with a knife in their boot and a dream in their heart. The term actually didn’t even exist until 1959, when a Pennsylvania folklorist needed a catchy title for a magazine piece and landed on “Tramp Work.” (You can read a scan of that magazine right here – the dressing cabinet on page 6 is to die for.)

But the name stuck, and for decades, people (including yours truly) pictured men carving frames beside campfires, swapping chip carvings for bread. It’s a good story! …just not the right one. The real makers were settled folks: farmers, factory workers, miners, carpenters, shopkeepers. They were normal people who sat down at night and made things because it felt good to make things. Some carved a single frame in their lifetime; others built entire bedroom sets from cigar boxes.

1900s Tramp Art Mirror, $1,250 | Tramp Art Mirror with Geometric Motifs, $2,750

Many were immigrants, especially from Germany and Scandinavia, who’d brought the centuries-old European tradition of chip carving that’d once been used to decorate peasant furniture. They applied those skills to the American waste stream of discarded cigar boxes and packing crates, landing on a new type of folk adaptation: an old-world art meeting new-world excess. (Feels like we could use a bit of this ethos today, don’t you think?)

The “tramp” myth stuck partly because it flatters us – we like our folk heroes poor, wandering, and pure of heart. It also let serious collectors treat the Tramp work like charming outsider junk instead of acknowledging that working-class men – many of them immigrants, some even prisoners – were making serious, time-intensive, technically sophisticated decorative art inside the home. So the story of Tramp Art isn’t one of a wandering, romantic poverty – it’s about staying put, working with what you have, and making it beautiful anyway.

Wait, Why Cigars?

Nautical Tramp Art Desk, $6,000

This all comes back to the IRS.

In 1864, the U.S. government started taxing cigars in an attempt to raise funds for the Civil War. And our bureaucrats did what bureaucrats do best: they invented a bunch of annoying paperwork that unintentionally rendered good wood worthless.

Every cigar had to be sold in a wooden box, sealed with an official revenue stamp. Once opened, the box was done – the stamp couldn’t be reused; the box couldn’t legally be sold again. Every puff of tobacco created a small pile of perfectly usable trash: sheets of Spanish cedar and mahogany, ripe for reuse. Men at home took one look at the pile and thought, I can work with this.

And for the next seventy years – between 1870 and 1940 – they did! Those wood scraps became jewelry boxes, frames, and furniture. When packaging shifted to cardboard and cellophane in the 1940s, the steady stream of scrap dried up, and the art form went quiet.

Seeing the Humanity

1900 Tramp Art Cabinet, $1,785

A few other things happened between 1870 and 1940 – a series of farm busts, Prohibition, and a little economic collapse called “The Great Depression” that reinforced America’s moral obsession with productivity. Men who were out of work or in seasonal jobs were under enormous pressure to stay busy, and carving became an acceptable kind of stillness.

Sitting at the table after dinner, knife in hand, cutting small V-shaped notches into the sides of old cigar boxes was a way to stay respectable, to keep the hands moving when the world had stopped offering work.

Carved Tramp Art Box, $1200 | 19th-century Tramp Art Box, $695

The motifs tell you everything: hearts for love; sunflowers for nature, care, and constancy; anchors for work, identity, and pride in trade; crosses and shrines for faith, memorial, grief. Some of it was sweet. Some of it was devotional. And some of it was exactly what it looked like: I love my wife, so I spent weeks carving her a jewelry box out of cigar boxes instead of drinking.

I think this is what I love most about Tramp Art – the mix of ego and devotion. The idea that you have the talent to build something beautiful, and the determination to spend weeks bringing that vision to life. The work isn’t minimalist, it’s not traditionally tasteful, and it’s definitely not ironic. It’s “I love my family, I love my country, I love God, and I own a pocketknife.” It’s personal. It’s earnest. It’s true. And aren’t those traits defining characteristics of all great art?

Condition, Value, and Why It Costs $75,000 Now

Late 1800s Tramp Art Mirror, $18,364.16

For most of the twentieth century, Tramp Art was the hillbilly cousin of American folk art. Dealers sold it from cardboard boxes for beer money; art experts called it “tacky,” “too much,” or “overdone.” (Translation: working class hands made this.) The fancy museums didn’t want it. You could practically hear the class bias humming: “real art” was marble and restraint, not a mirror made from old cigar boxes. For decades, no one looked twice – until the research caught up.

In the 1970s, an antiques expert named Helaine Fendelman began tracking Tramp Art makers – actual names, lives, places – and began to prove that these men weren’t hobos by a campfire. Her books and early shows were the first time anyone treated the work like design history instead of roadside kitsch. Once the myth cracked, scholars began paying attention.

Tramp Art Cabinet, $75,000 | Tramp Art Chess Set, $18,500

Fast-forward forty years: in 2017, the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe opened No Idle Hands: The Myths and Meanings of Tramp Art. More than 150 pieces filled the galleries – boxes! Frames! Clocks! Dressers! – that had all been carved by working people from scrap. Curator Laura Addison made the case plainly: this wasn’t “hobo junk”; it was a material record of thrift, faith, and discipline in America.

That show flipped the market. Overnight, the stuff that once sold for gas money became institutional. Collectors realized these weren’t curios – they were blue-collar masterpieces. Now, the spread runs wide. A rough jewelry box or frame might still be a hundred bucks (I can confirm – just bought a busted frame from the Pierce & Ward warehouse sale for a hundred smackers!). A painted piece or a clean frame can hit the low thousands. Anything with a named maker lands higher. And the bigger pieces of furniture? The multi-year projects built from hundreds of boxes? Those are five-figure objects. (Top sales are currently hovering around $75,000.)

How I Look at Tramp Art Now

Late 1800s Tramp Art Mirror, $3,800 | 1890s Tramp Art Box, $2,400

ALRIGHT, I KNOW I’M VERY SENTIMENTAL. But I think you have to love objects this deeply if you’re going to make a living yapping about them on the internet! Let me take it home: Tramp Art is a documentary practice. Every piece is a ledger of American life – who was here, what they valued, and how they worked when there wasn’t much work to be had.

It’s a tradition that came from men who knew how to carve before they ever got here – immigrants who’d learned chip-carving in Germany, Norway, Austria, Poland – and who turned that skill loose on cigar boxes because that’s what was around. It exists because the government, in its post-war bureaucracy, accidentally flooded the nation with free mahogany. (I wouldn’t mind if this happened today, to be honest.) And it survived because people had to keep their hands moving, whether they were out of work, stuck at home, or locked up.

And it’s personal! You can read a lot in the details if you slow down long enough. The hearts, anchors, crosses, and flowers carved into these pieces are the same visual shorthand found on quilts, gravestones, and tattoos: love, work, faith, remembrance. Tramp Art offered self-expression to people who had few other creative outlets.

The art world ignored it for the same reason it ignored most labor: it was domestic, repetitive, and made from trash. Too much carving, too much pattern, too much emotion. But the joke’s on minimalism – strip the context and Tramp Art is modular, symmetrical, deeply engineered, and conceptually ahead of its time.

I think that’s what gets missed when people call it kitsch – fine art has always relied on the illusion that materials confer legitimacy. Oil paint means mastery, bronze infers permanence, marble implies worth. Tramp Art dismantles that idea. It proves that form, balance, and imagination are medium-agnostic – that the same compositional intelligence can live in cedar scraps as easily as in cast metal. It’s not craft pretending to be art; it’s art that happens to be honest about what it’s made from. (We just decided to deem it “folk” because we couldn’t imagine fine art being made by someone in a work shirt. At some point in our cultural history, we decided that fine art only counted when it came from men in Paris instead of men in Pennsylvania.)

So the next time you walk through an antique mall and see one of those dark, layered, spiky frames leaning in a corner, don’t walk past. It’s not clutter. That’s somebody’s winter of 1933 – and, in its own way, a national record.

The Part Where You Learn The Process

Set of Hermitage Boxes, $2,530

Wow, you read all that! Feeling ready to pick up a new hobby? Tramp Art won’t break the bank! A quick beginner’s guide to get you started. Grab your pocket knife, a wood scrap, and infinite patience – that’s really all it takes.

The Notch

This is the signature move. Every piece begins with a notch – the tiny V-shaped cut made by a pocketknife. Notches march down the edge of each strip of wood like stitches, perfectly even, even though they were eyeballed by hand. No rulers, no instructions, no pattern books – just quiet carving to the sound of the radio.

Layering

Once you’ve notched your strips, you start stacking them – big pieces at the bottom, smaller ones on top, layering one atop another til the pieces’s stacked up like a Ziggurat. The real miracle here isn’t precision – it’s actually restraint! The layering process gives the illusion of weight, but the whole thing might weigh less than a house cat, like a sculpture made from air.

The (Sometimes) Secret Skeleton

Here’s what most people (read: me) don’t realize: the big furniture – the dressers, cabinets, desks – isn’t solid Tramp Art. As it turns out, you cannot make a wardrobe out of cigar boxes alone.

Underneath all the spiky ornament is a hidden frame, usually built from sturdier wood like pine or poplar (often pulled from reclaimed shipping crates). That’s what holds the weight. The carved layers are cladding – a decorative shell wrapped around a solid, sensible core.

How to Read the Clues

Every material tells a story…if you know how to read the clues.

- Nails: hand-cut nails can date a piece to the 19th century; machine-made nails date to the early 20th century; wire nails mean somebody’s been messing around with restoration.

- Glue: hide glue is the real deal – brittle, brown, slightly sweet-smelling. Anything shiny or foamy means that the piece has been updated.

- Tax stamps: Remember that whole IRS shenanigan? Those official revenue stamps are sometimes still present on the backs or bottoms of Tramp Art pieces, and they’re the ultimate fast-track to identifying the provenance of your piece. (You can fake patina, but you can’t fake the IRS).

I hereby present to you my very own, very damaged, very beautiful aforementioned Tramp Art frame. (ICYMI, I sprinted to buy this for $100 at Pierce & Ward’s recent warehouse sale.) She’s not perfect by any stretch of the imagination – it’s missing entire sections; there’s no shortage of cracks; some of the sections had to be physically reattached – but it’s still one of my favorite possessions. I love thinking about the person who made it, and it’s an honor to steward it into the next generation. (I imagine I’ll like it even more once I’ve put a picture in it! It brings so much joy!)

What say you? Has the myth been busted? Are you joining me on the Tramp Art train? (Hobos welcome, obviously.) LET’S TALK ABOUT IT! Happy weekend. 🙂 xx

Opening Image Credit: Photo by Kaitlin Green

Thank you for shining a light on this intricate artform, Caitlyn! You’ve got me interested in the book and the first art exhibit! I am confused about the distinctions made between homeless people and working class, and why that changed the value of the art. Many “tramps” were simply people who didn’t own property, and worked any odd job they could find, moving on to the next town when the work ran out. Who’s to say that they didn’t also have faith, weren’t disciplined, or thrifty? I would argue that they may have had those qualities in spades to do what they did, without the comfort or convenience of staying at home. Who’s to say that settlers wouldn’t have also traveled for work if they weren’t tied to property and families? Who’s to say that out-of-work folks who hadn’t yet lost their homes were more “normal” than those who had? Weren’t there travelers who left their families to make some money to bring back home? If the “tramps” *had* carved art, wouldn’t that be even more valuable, considering their circumstances? It sounds like the valuation remains classist, or at least did for awhile after the myth was busted. Not necessarily… Read more »

Thank you so much for this fascinating essay! I shared this with several family members already, I LOVE this kind of post!

Fascinating, and so well written!

I first saw this kind of work at an exhibition at the Oakland Museum of Art in the 90s, and it’s kind of crazy to see its trajectory from the margins of “outsider art” to the coolest trendsetters’ homes.

I’m now thinking that the trend of using pallets as furniture-building material, which I really dislike because it’s terrible wood that’s been chemically treated, is sort of the modern day version of tramp art. Maybe?

I also want to thank you for this incredibly written, researched and funny article.

Interesting. I would tend to disagree because pallet pieces were/are more functional (at least the ones I have seen) vs this work that seems more focused on the form and beauty. But maybe that’s a reflection of an overall decline in skills and aesthetics?

I could see that. Also, there is tramp art furniture, just as there are decor-type pieces made from pallets. I think the people who indulge in that particular type of DIY have to believe the work is beautiful in some way, even if I don’t personally agree.

What a fascinating article. And a shout out for the Santa Fe Folk Art museum, it’s one of my favorite museums of all time.

THIS WAS SO EFFING EDUCATIONAL AND FUN! I loved learning about this! Thank you! 🙂

Interesting read! Thx!

When I was little I would go to antique malls with my grandma and mom. I always loved Tramp Art. I have a few picture frames. My 18 year old son, who’s kind of a cool skater kid, also loves it and has wanted a box. Boxes have gotten pretty expensive, but I managed to get one at a local auction just yesterday! I bid a little higher than I wanted to, but I still got it for a reasonable price. I’m saving it for his Christmas present! I’m just happy my kid shares my love of weird vintage items.

This is amazing, Liz!

Caitlin! Your articles are always so fascinating! My favorite is the one on American Quilts-incredible. Ok, two things can be true at the same time. I am an artist, interior designer, design junkie, quilt collector 😉 and I’ve got a beautiful tramp art box, much like the ones you have shown in this article, in my will, from my 90 year old grandfather. He’s still alive, but when he passes, he wants that beautiful box to go to me. (Tears!) He told me this history of it with names from ALL our family history! Everything is written down and documented. The tramp art box dates back to the 1700s. My grandfather and all our family are from Pennsylvania! So…my great great great grandfather was wealthy, and he and his wife would allow people who were homeless to live in their barn, only for a few days at a time, so they could generously feed the next round of homeless people. In exchange for their kindness, they were given all sorts of “tramp art” like this, made by the less fortunate. So while I agree with you that anyone could sit down by their fire at night and whittle away and… Read more »

What a treasure of history to have, Elizabeth!

Dani! I know 🥹SUCH a treasure!!

This essay really got me, full of fondness for humanity and our desire/compulsion to create, to carve, to doodle, to knit, to sing…to add meaning and beauty to our lives. Thank you, Caitlin! I always enjoy your writing and thoughts so much!

What a beautiful, lyrical, well-researched, and persuasive essay. Thank you for opening my eyes to this art form that l knew nothing about an hour ago.

Caitlin – I really hope you have a book of essays or a novel in the works because your writing is funny, sophisticated, and insightful!

I have genuinely never heard of Tramp Art before. When I saw the title I thought it was going to be about Sara Tramp’s art collection, or maybe that she was making artworks.

Very very interesting and educational!!!

Thank you for this! It reminds me of your piece on the Gee’s Bend quilts and quilters – my favorite from the archives – and I hope it inspires a regular series on homegrown craft. And then a book 🙂

I had no idea! What an informative and interesting post!

Check out the Lone Fox video “Tramp Art is ALL THE CRAZE! Can I DIY It? (3 projects)” if you want to try making it yourself. Nothing elaborate, but it’s a start.

What an interesting read! Thank you, Caitlin!

When I saw ‘tramp art’ in the title I knew we were in for a Caitlyn deep dive and it did not disappoint! Thank you so much for this. Your passion is infectious as always.

Caitlyn!!! What an amazing article! I knew nothing about tramp art And now I can’t wait to look for some. As usual, you’re writing is truly enjoyable. Thank you for this!

This was truly a fun ride to take today!

Fascinating! Thank you!!

You, like your Tramp Art, are a true treasure.

Loved this, and learned so much. Also, as the wife of someone who was out of work for much of 2020 due to COVID shutdowns, I really, really related to the idea of men needing to do something with their hands when work outside the home dried up. While he was out of work, my husband built corn hole boards for our boys out of scrap wood, and then he spent days painting them. They are gorgeous. They are also precious to me, because he chose to do something lovely for the good of our family instead of drowning his worries in booze, which is probably what he really wanted to do.

Wow, to echo everyone else, this was a really incredible piece, Caitlyn! Love your deep dives on these fascinating subjects – I always learn a lot. Thank you for all you do!

I knew some of this, but not all, so thank you for the education!

I love this kind of piece so much! Thank you for writing it. More essays like this please from Caitlin!

I love this article! I had heard the term tramp art applied to some picture frames, but didn’t know anything beyond that. I hope you get to keep writing articles like this for a long time. This makes me really want to visit the Sante Fe Folk Art museum someday, too!

Love this smart, thoughtful, elegant article soooo much. I’m familiar with folk art quilting and painting but Tramp Art is brand new to me. Thank you for the writing and for the new art to love!

Caitlin should write a book! With each chapter a story like this!

Fantastic read, so incredibly interesting! I love it when art from women and the working class (what’s normally relegated to “craft;” you could write a whole article on the connotation of that word) gets its due. Tramp art has been on my radar more and more, and I’ve been noticing it more at antique fairs, but I fantasize about finding some gorgeous hidden gem tucked away at a thrift store because no one realized what it was (isn’t that always the dream??).

That is a fascinating article! I really never knew any of that! I’ve had a box of modern day thin wooden Cigar Boxes for about 20 years that I’ve meant to decorate. They aren’t substantial enough to carve or make furniture out of. At least I don’t think so.

I now have a wider view of what COULD be done with them though.

I’m going to look for some Tramp Art now.

Thank you for this History lesson.

This is SO COOL!!! I’d never heard of tramp art before, so loved getting to go right into this deep dive.

Gah! Such a great read!! Thank you for this wonderful history lesson. I have a new appreciation for this art for sure now.